The hill-tracts areas around Mainamati - Lalmai in Comilla district has a long ancient history of its own. This post is about some historical sculptures of these areas before the 9th century. The Comilla district is located in the South-East part of the Bangladesh, including other districts in this zone such as Chittagong, Noakhali, Barishal, Feni, Chandpur and some other districts around these, which was once called the Southeast Bengal.

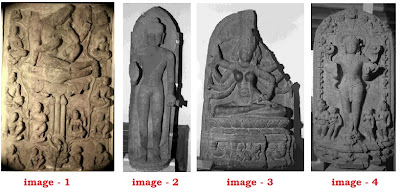

It is difficult to define with precision the style of stone sculptures prior to 9th century. in Southeast Bengal due to the utmost rarity of the images then carved. Those available differ, however, from the early north Bengal school in giving greater importance to the line, and thus to the proximity of the divine nature rather than in underlying its distance from the worshipers through a hierarchic un-moving icon (image-1 and image-2 in screenshot-1). Take a look at the images below:

Screenshot - 1:

The volumes are softly modeled, the lines fluid and elegant, and the ornamentation is practically in existent thus the divine nature shows itself in all its compassion and generosity, with smooth smile, slightly closed eyes, smooth gestures, it is extremely close to the devotee although it imposes itself through its dignity. These images were found on the Lalmai- Mainamati range in Comilla District, which imposes itself to the voyager coming from the West, i.e. from ancient Vikramapura, and this explains why the stylistic development will be henceforth entirely related to the school of sculpture which develops in the old capital and its surroundings, being located only 70 km far-off from Lalmai-Mainamati.

Images which can be dated back to the 9th or even 10th century, betray a strong relationship to Magadha, the stone in which they have been carved as well as their style suggest that either the material or the finished image might have been imported from the region, which thus reflects a situation encountered at the same period in North Bengal (image-3 in screenshot-1). The importance of such sculptures is not to be underestimated for they did not only introduce particular iconography types, they also constituted a model allowing to understand the divine nature and its relationship to the, i.e. our, world emanating out of it.

The deity is depicted in full splendor and expressing his / her power by hiding the bare back-slab where only the edge is adorned with flames and a border of pearls, indicating the aureole, sitting or standing above a pedestal where the devotees, who were also the donors, are pre-eminently depicted. The jewelry, the dresses, and the head-dresses are carved with utmost meticulousness. The forms are round, well drawn through elegant and smooth lines; the faces are slightly fleshy, showing a subtle smile, the eyes are half opened.

With the bareness of their back-slab which underlines the presence of the deity, those images lead to the first of the three stylistic idioms which developed in the region of Vikramapura in the 11th and 12th centuries, (image-4 in screenshot-1). The body is slender, the head-dress elongated, the waist and shoulders are narrow. Like in North Bengal, the ornamentation is over-abundant although some of the jewellery / ornaments can present a different form (see for instance the girdle with a double row of loops and pendants). Attending figures stand on either side of the deity, not in the stiffened attitude of the central image, but slightly bent.

The pedestal is inserted within the composition of the part of the sculpture which it sustains and does not constitute an independent unit as seen in other stylistic idiom. The whole composition is evidently based on more fluidity between the different parts of the images (deity, attendants, back-slab, and pedestal) at the same time that it does not illustrate any separation between the deity and the human world symbolically represented by the pedestal – where devotees are usually represented (image-5, 6 and 7 in screenshot-2). In a certain way, this trend rediscovers the possibility of making the deity present through its sole presence, as observed at Paharpur in the 8th century.

Images which can be dated back to the 9th or even 10th century, betray a strong relationship to Magadha, the stone in which they have been carved as well as their style suggest that either the material or the finished image might have been imported from the region, which thus reflects a situation encountered at the same period in North Bengal (image-3 in screenshot-1). The importance of such sculptures is not to be underestimated for they did not only introduce particular iconography types, they also constituted a model allowing to understand the divine nature and its relationship to the, i.e. our, world emanating out of it.

The deity is depicted in full splendor and expressing his / her power by hiding the bare back-slab where only the edge is adorned with flames and a border of pearls, indicating the aureole, sitting or standing above a pedestal where the devotees, who were also the donors, are pre-eminently depicted. The jewelry, the dresses, and the head-dresses are carved with utmost meticulousness. The forms are round, well drawn through elegant and smooth lines; the faces are slightly fleshy, showing a subtle smile, the eyes are half opened.

With the bareness of their back-slab which underlines the presence of the deity, those images lead to the first of the three stylistic idioms which developed in the region of Vikramapura in the 11th and 12th centuries, (image-4 in screenshot-1). The body is slender, the head-dress elongated, the waist and shoulders are narrow. Like in North Bengal, the ornamentation is over-abundant although some of the jewellery / ornaments can present a different form (see for instance the girdle with a double row of loops and pendants). Attending figures stand on either side of the deity, not in the stiffened attitude of the central image, but slightly bent.

The pedestal is inserted within the composition of the part of the sculpture which it sustains and does not constitute an independent unit as seen in other stylistic idiom. The whole composition is evidently based on more fluidity between the different parts of the images (deity, attendants, back-slab, and pedestal) at the same time that it does not illustrate any separation between the deity and the human world symbolically represented by the pedestal – where devotees are usually represented (image-5, 6 and 7 in screenshot-2). In a certain way, this trend rediscovers the possibility of making the deity present through its sole presence, as observed at Paharpur in the 8th century.

Screenshot - 2:

Simultaneously and while preserving the slenderness of the body of the previous group; another stylistic idiom works out the back-slab as observed in the North (image-5 and image-6 in screenshot-2). Carved in low-relief, the well-organized ornamentation harmonizes with the high relieved images of the deity and attendants; the motifs are well-drawn and delimited from each other. The face shows eyes sloping slightly upwards, the mouth follows the same upwards direction, the chin is small; the body is elongated, undisturbed, clearly shaped on the back-slab which can eventually be open. This opening creates a new space, the limits of which remain unknown, and out of which the deity seems to emerge, as an image of certitude which expresses its creative potentialities through the presence of the pyramid of animals seen on the back-slab, or through the miniaturized representations of groups of deities related to the main one (Âditiyas, Avatâras, etc.) – a feature that appears to be a peculiarity of the South-eastern ateliers.

The sculpture is thus perceived as a maṇḍala with the central axis being the main image around which the tiny representations irradiate (image-7 in screenshot-2). Such an understanding of the deity, as ruling over the universe, contributes to create a rather abstract image which practically locates the devotees at the outskirt and lets out the representation of the creation in all its splendor and richness as testified on 11th-12th centuries. images of North Bengal.

However, this Northern trend found also its way in the region of Vikramapura, particularly in the 12th century. (image-5 in screenshot-2). As a matter of fact, we find images where the concept of the god positioned at the center of the universe and surrounded by tiny representations of other deities or of himself has been preserved and merged with the idea of the creation born out of the deity. The back-slab combines both concepts, being, as a result, completely covered by the ornamentation (image-6, image-7 in screenshot-2). However, the motifs are clearly separated, the lines are strongly marked, and the artists introduced different depths in the carving of the ornamentation, thus accentuating the dramaturgy: the animals of the royal throne and the avatar’s are carved on low relief on either side of the god, the divine garland-bearers and the monstrous face show more depth; the creation and the universe centered on the deity are clearly displayed in the back-ground.

On the contrary, the attendants and the vehicle are carved in high-relief, being parts of the divine personality. Also in the 12th century, (image-6, image-7 in screenshot-2), the taste for reflecting the gorgeousness of the creation through an utmost detailed carving and a very nervous line in the rendering of tiny motifs – a trend essentially developed in North Bengal – is present; it does, however, blend with the regional fundamental tendency towards distinctness, preserving bare spaces on the back-slab which enhance the crisp and intricate ornamentation.

A particular and limited aspect of this stylistic idiom deserves to be noted, which exclusively comprehends 11th & 12th centuries, images of the Buddha which have been found from Dhaka to Chittagong, and relate to some of the cast images found at Jhewari (image-8 in screenshot-2). It does preserve a clear structure, allowing a perfect reading of a rather complicated iconography which betrays the existence of contacts with Pagan. Such an image shares with the Brahmanical images from Vikramapura the introduction on the back-slab of small divine representations: of the Buddha himself and of the Buddhas of the past here, of the avatāras, the Āditiyas, or the Dikpālas on the Brahmanical images. The heaviness of the limbs, however, like the facial features of the Buddha remind more of his images in Pagan.

Thus the school of Southeast Bengal emerged with its own conception of style where the clearly drawn composition contributes to emphasize the distance between the deity and the world on which he/she rules. Although the evolution runs parallel to the way followed in the North, showing taste for an utmost refined carving, this notion will remain basic through all the development.

The sculpture is thus perceived as a maṇḍala with the central axis being the main image around which the tiny representations irradiate (image-7 in screenshot-2). Such an understanding of the deity, as ruling over the universe, contributes to create a rather abstract image which practically locates the devotees at the outskirt and lets out the representation of the creation in all its splendor and richness as testified on 11th-12th centuries. images of North Bengal.

However, this Northern trend found also its way in the region of Vikramapura, particularly in the 12th century. (image-5 in screenshot-2). As a matter of fact, we find images where the concept of the god positioned at the center of the universe and surrounded by tiny representations of other deities or of himself has been preserved and merged with the idea of the creation born out of the deity. The back-slab combines both concepts, being, as a result, completely covered by the ornamentation (image-6, image-7 in screenshot-2). However, the motifs are clearly separated, the lines are strongly marked, and the artists introduced different depths in the carving of the ornamentation, thus accentuating the dramaturgy: the animals of the royal throne and the avatar’s are carved on low relief on either side of the god, the divine garland-bearers and the monstrous face show more depth; the creation and the universe centered on the deity are clearly displayed in the back-ground.

On the contrary, the attendants and the vehicle are carved in high-relief, being parts of the divine personality. Also in the 12th century, (image-6, image-7 in screenshot-2), the taste for reflecting the gorgeousness of the creation through an utmost detailed carving and a very nervous line in the rendering of tiny motifs – a trend essentially developed in North Bengal – is present; it does, however, blend with the regional fundamental tendency towards distinctness, preserving bare spaces on the back-slab which enhance the crisp and intricate ornamentation.

A particular and limited aspect of this stylistic idiom deserves to be noted, which exclusively comprehends 11th & 12th centuries, images of the Buddha which have been found from Dhaka to Chittagong, and relate to some of the cast images found at Jhewari (image-8 in screenshot-2). It does preserve a clear structure, allowing a perfect reading of a rather complicated iconography which betrays the existence of contacts with Pagan. Such an image shares with the Brahmanical images from Vikramapura the introduction on the back-slab of small divine representations: of the Buddha himself and of the Buddhas of the past here, of the avatāras, the Āditiyas, or the Dikpālas on the Brahmanical images. The heaviness of the limbs, however, like the facial features of the Buddha remind more of his images in Pagan.

Thus the school of Southeast Bengal emerged with its own conception of style where the clearly drawn composition contributes to emphasize the distance between the deity and the world on which he/she rules. Although the evolution runs parallel to the way followed in the North, showing taste for an utmost refined carving, this notion will remain basic through all the development.

source: "The Sculpture of Bengal", a stylistic History from the 2nd c. BC till the 12th c. AD, Claudine Bautze-Picron, C.N.R.S., Paris

Thanks a lot for reading this.

other related posts:

Cast Images - History and Sculptures of Mainamati-Lalmai - Part 2

History and Sculptures of Mainamati-Lalmai in Comilla - Part 3

Little History of SouthEast Bengal - Conquest and Culture Changes

A little about Comilla District

Bangladesh Census Report - 2011 for Comilla

Total 16 Upazilas under Comilla District

Famous Persons from Comilla Region

No comments:

Post a Comment